After 11 years, a perfect storm around the new coronavirus has pushed markets into bear territory. The World Health Organization officially declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic, markets were disappointed by government policy responses, and containment measures increased as cases continue to rise globally. Given the swiftness by which the coronavirus has spread and of the market decline, it’s only natural to have concerns about your portfolio. It’s also important to keep a few key facts in perspective.

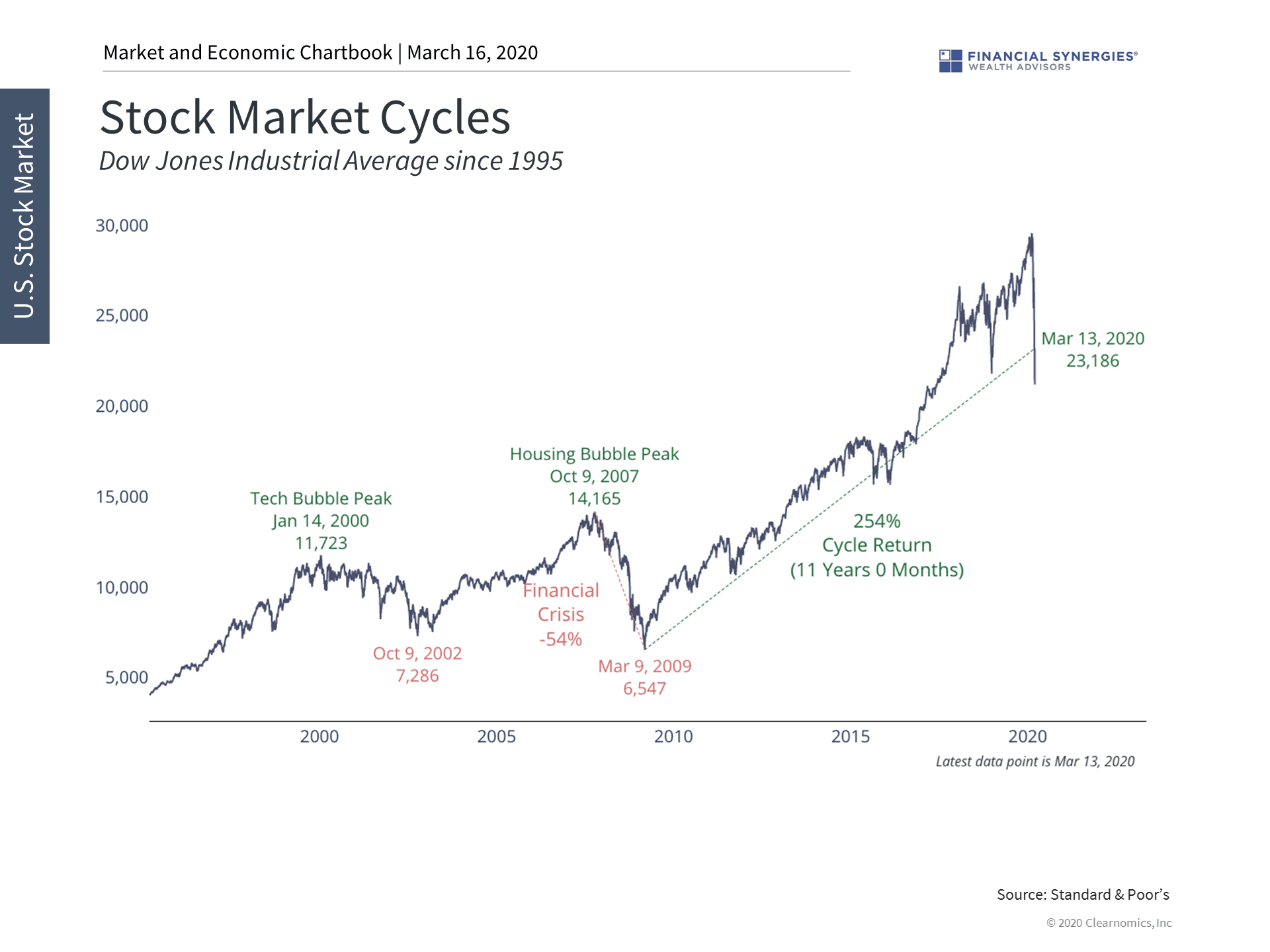

First, at the risk of debating semantics, it’s important to discuss definitions. Just as the WHO is careful and deliberate when declaring an outbreak of disease a pandemic, we should be careful in clarifying what it means to be in a bear market. A commonly-agreed-upon definition is that a bear market is a 20% decline in a broad market index from its peak. The Dow Jones closed yesterday with a peak-to-trough decline well over 20% and other major indices have followed.

While a 20% decline does meet the dictionary definition and trigger bear market headlines, the spirit of the term is of a protracted period of deep market weakness and uncertainty which is almost always tied to an economic recession. Case in point: the average bear market since World War II experiences a market decline of 35%, far worse than the standard 20% definition.

This is important because we have seen several near-20% pullbacks in recent years – first in 2011 when the U.S. debt was downgraded, then in late 2018 when many economists were forecasting an imminent recession. This is where the semantics become tricky. Is a 19.8% decline (September to December 2018) materially different from 20%? Should we call it a bear market if it recovers within months?

This doesn’t mean that any market pullback is pleasant or that the situation can’t deteriorate. It’s simply a reminder that we’ve seen similar declines before, regardless of what we call them.

Second, it isn’t the label that causes markets to fall – it’s the underlying fundamental cause. In this case, the spread of coronavirus has been swift, resulting in aggressive government actions. In many ways, slowing the spread via social distancing and other measures is an attempt to immunize society, but with side effects that harm the economy.

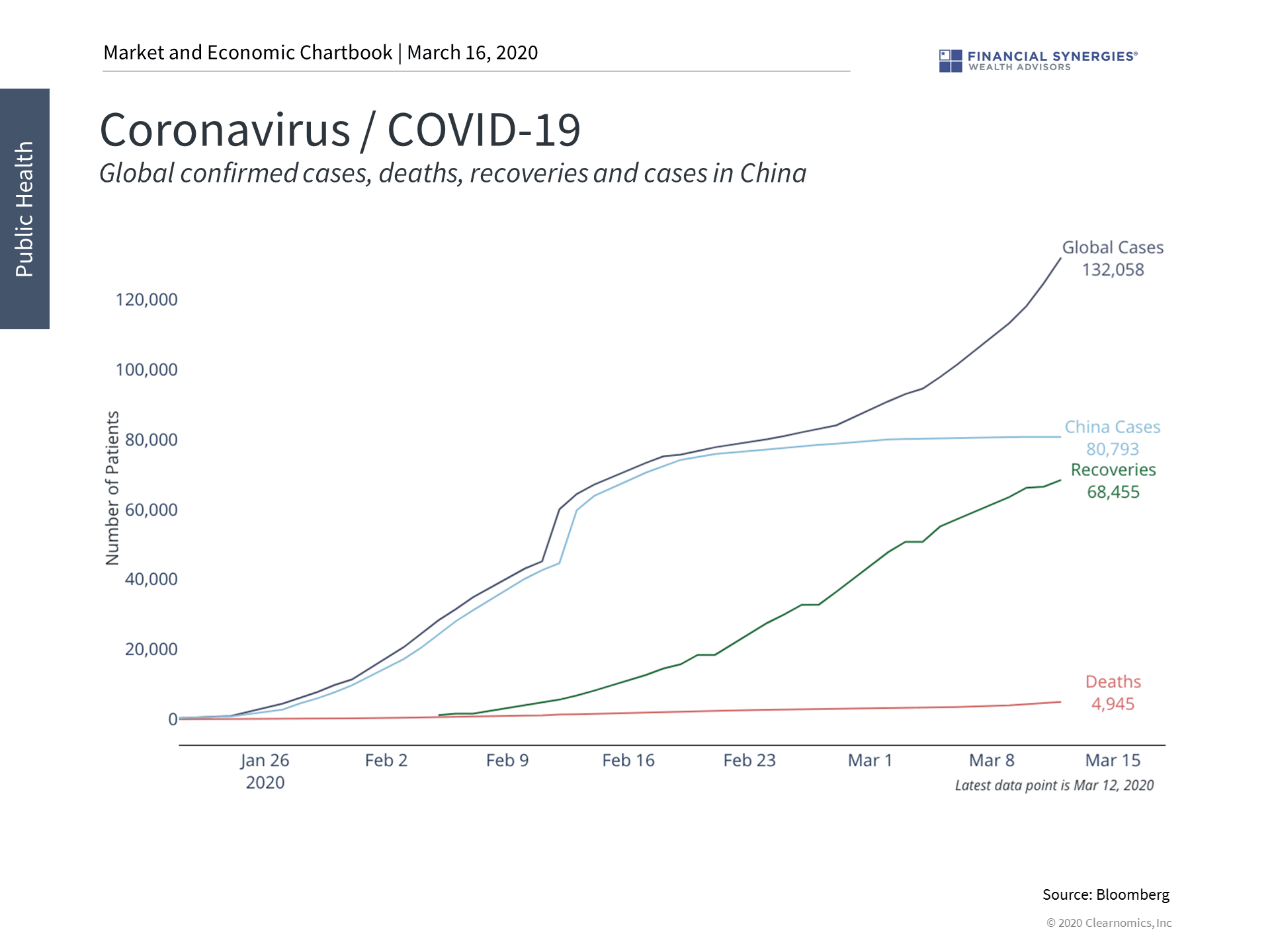

At the moment, based on the available data, it appears that the rise in global confirmed cases is accelerating even as new cases in China have flat-lined. Going forward, there are a wide range of possible outcomes depending on government and the health sector actions.

This is the heart of the issue. Markets are built to “price in” all available information. It’s true that if the economy is disrupted then growth, profits and cash flows may fall. However, the bigger problem is that significant uncertainty, especially in the absence of relevant historical guidance, makes it difficult to assign a value to investment assets.

In technical finance terms: the discount rate is high. In simple terms: it’s hard to know what to pay today to receive $1 in the future because it’s very unclear what that future may look like.

So, what do we know?

We know that the U.S. economy was very strong prior to the coronavirus outbreak, increasing its likelihood of recovery.

We know that the cause of this bear market isn’t inherent to the economy or the financial system. This isn’t 2008 when financial markets seized up or 2000 when valuations were at astronomical levels. There are scenarios where short-term liquidity problems can become long-term solvency issues, but we’re not there yet.

We know that we will see poor economic readings over the next several months and possibly quarters. This should not be a surprise when it happens. Be ready.

We know that markets will be sensitive to headlines and government policies in the short run. Ideas such as payroll tax relief, delayed tax filings, small business loans and more could help minimize the economic impact. And the Fed has already essentially cut rates to zero.

Finally, and most importantly, we know how investors can navigate significant periods of uncertainty, regardless of the catalyst. Holding diversified portfolios that are appropriately tailored to an investor’s financial goals is the best way to navigate any type of market. Having a smoother ride allows you to handle the bumps in the road without having to swerve around each pothole.

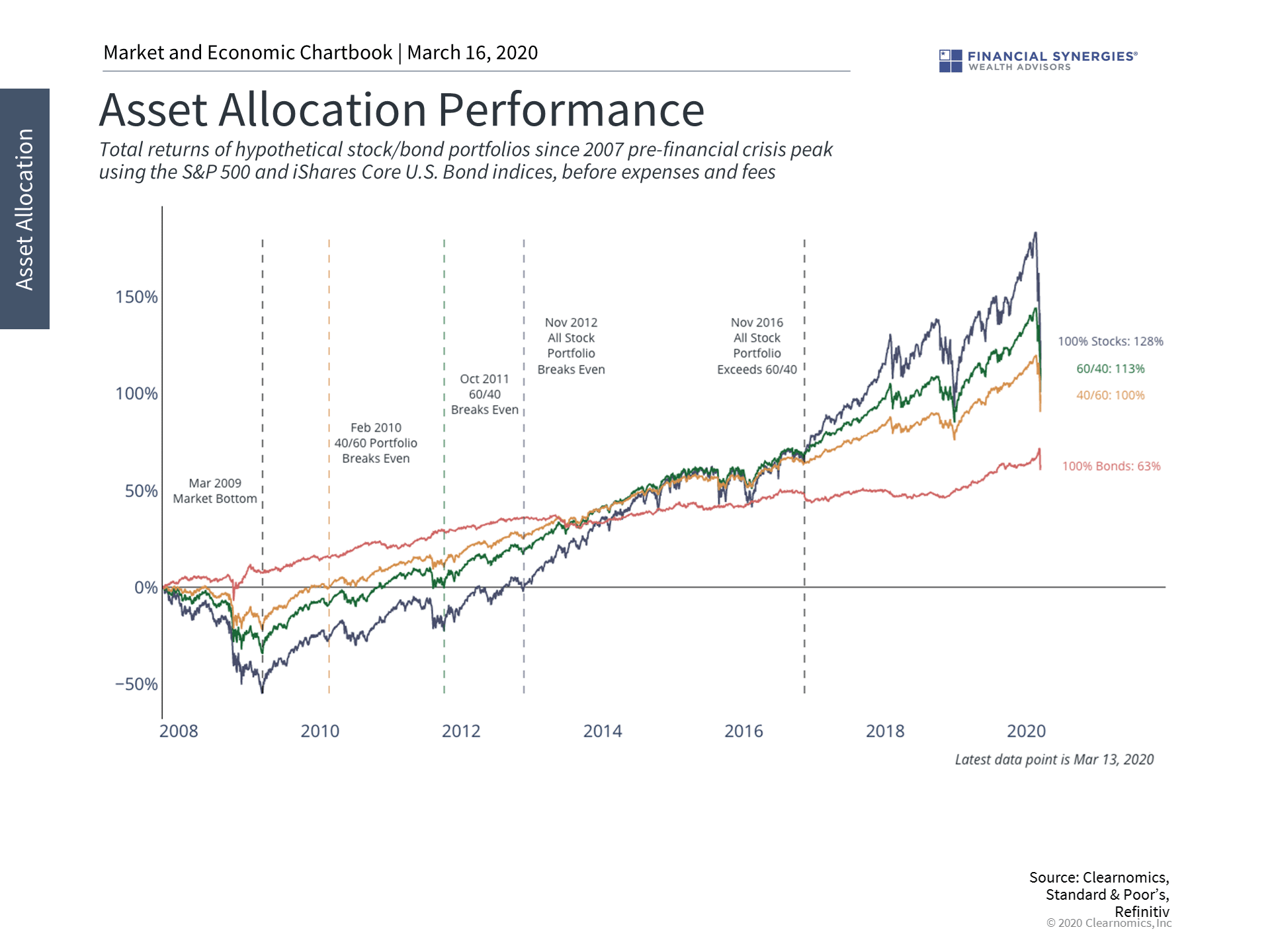

The first chart below dissects how various asset allocations performed following the 2008 financial crisis. An all-stock portfolio with reinvested dividends may have done very well until 2007, but would have fallen by nearly half in March 2009. And while it did recover steadily from there, it took until late 2012 to climb out of this deep hole. The biggest problem would have been the temptation to change course at every point along the way.

This is where being diversified can help. A portfolio consisting of 60% bonds and 40% stocks recovered its full value in only 11 months from the market bottom – an amazing fact. It has performed well since then, even keeping pace with the all-stock portfolio through late 2016. By definition, it has also declined far less in recent weeks.

That being said, for younger investors an all-stock portfolio can definitely pay off handsomely over the long-run because of the sheer number of years invested.

A more aggressive portfolio consisting of 60% stocks and 40% bonds would have recovered by Oct 2011, about two and a half years after the bottom. It also kept pace with the all-stock portfolio until late 2016, and with recent market volatility, is still quite close.

Those who held only bonds for safety, rather than as an appropriate asset allocation, fared well in the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis. However, it’s clear that even in an unprecedented period of falling rates and policy easing, this portfolio provided little long-term growth.

While the future is uncertain and the causes unique, there have been many market pullbacks and bear markets in the past. In each case, the best response for long-term investors has been to hold diversified portfolios and stay the course.

Our portfolios are carefully crafted to prepare for exactly these events. Trusting in this preparation is the best approach for achieving financial goals.

Below are four charts that help to put the bear market pullback in perspective.

1. Diversification is the best way to immunize a portfolio against uncertainty

Different asset allocations performed uniquely after the global financial crisis. Holding a mix of stocks and bonds not only helped to cushion the initial fall, resulting in a faster recovery, but kept pace with an all-stock portfolio for years. Balanced portfolios have also helped to stabilize investor returns in recent weeks.

2. The spread of coronavirus is still uncertain

Global confirmed cases of COVID-19 have accelerated as the coronavirus spreads through Europe and now the U.S. Health officials have communicated that the path of the lines above will depend heavily on the public response. This has created significant uncertainty for markets and investors.

3. Major indices are officially in bear market territory

Major stock market indices fell into bear market territory last week – commonly defined as a decline of 20% from recent peaks. However, deep, prolonged bear markets often only occur alongside recessions and protracted economic weakness. While this is possible depending on the outcome of the coronavirus, we are not at that point just yet.

4. It’s important to keep this market decline in perspective

It’s important to keep this bear market pullback in perspective. Historical bear markets have been much worse because of economic weakness. Still, even with the tech bubble and 2008 financial crisis, markets tend to recover once there is clarity and growth resumes. Long-term investors seeking to achieve financial goals over years and decades should keep recent market swings in context, shown in the chart above.

As the old cliche goes, “it will probably get worse before it gets better.” But, it WILL get better.

Source: Clearnomics

What to Know About Bear Market Pullbacks

After 11 years, a perfect storm around the new coronavirus has pushed markets into bear territory. The World Health Organization officially declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic, markets were disappointed by government policy responses, and containment measures increased as cases continue to rise globally. Given the swiftness by which the coronavirus has spread and of the market decline, it’s only natural to have concerns about your portfolio. It’s also important to keep a few key facts in perspective.

First, at the risk of debating semantics, it’s important to discuss definitions. Just as the WHO is careful and deliberate when declaring an outbreak of disease a pandemic, we should be careful in clarifying what it means to be in a bear market. A commonly-agreed-upon definition is that a bear market is a 20% decline in a broad market index from its peak. The Dow Jones closed yesterday with a peak-to-trough decline well over 20% and other major indices have followed.

While a 20% decline does meet the dictionary definition and trigger bear market headlines, the spirit of the term is of a protracted period of deep market weakness and uncertainty which is almost always tied to an economic recession. Case in point: the average bear market since World War II experiences a market decline of 35%, far worse than the standard 20% definition.

This is important because we have seen several near-20% pullbacks in recent years – first in 2011 when the U.S. debt was downgraded, then in late 2018 when many economists were forecasting an imminent recession. This is where the semantics become tricky. Is a 19.8% decline (September to December 2018) materially different from 20%? Should we call it a bear market if it recovers within months?

This doesn’t mean that any market pullback is pleasant or that the situation can’t deteriorate. It’s simply a reminder that we’ve seen similar declines before, regardless of what we call them.

Second, it isn’t the label that causes markets to fall – it’s the underlying fundamental cause. In this case, the spread of coronavirus has been swift, resulting in aggressive government actions. In many ways, slowing the spread via social distancing and other measures is an attempt to immunize society, but with side effects that harm the economy.

At the moment, based on the available data, it appears that the rise in global confirmed cases is accelerating even as new cases in China have flat-lined. Going forward, there are a wide range of possible outcomes depending on government and the health sector actions.

This is the heart of the issue. Markets are built to “price in” all available information. It’s true that if the economy is disrupted then growth, profits and cash flows may fall. However, the bigger problem is that significant uncertainty, especially in the absence of relevant historical guidance, makes it difficult to assign a value to investment assets.

In technical finance terms: the discount rate is high. In simple terms: it’s hard to know what to pay today to receive $1 in the future because it’s very unclear what that future may look like.

So, what do we know?

We know that the U.S. economy was very strong prior to the coronavirus outbreak, increasing its likelihood of recovery.

We know that the cause of this bear market isn’t inherent to the economy or the financial system. This isn’t 2008 when financial markets seized up or 2000 when valuations were at astronomical levels. There are scenarios where short-term liquidity problems can become long-term solvency issues, but we’re not there yet.

We know that we will see poor economic readings over the next several months and possibly quarters. This should not be a surprise when it happens. Be ready.

We know that markets will be sensitive to headlines and government policies in the short run. Ideas such as payroll tax relief, delayed tax filings, small business loans and more could help minimize the economic impact. And the Fed has already essentially cut rates to zero.

Finally, and most importantly, we know how investors can navigate significant periods of uncertainty, regardless of the catalyst. Holding diversified portfolios that are appropriately tailored to an investor’s financial goals is the best way to navigate any type of market. Having a smoother ride allows you to handle the bumps in the road without having to swerve around each pothole.

The first chart below dissects how various asset allocations performed following the 2008 financial crisis. An all-stock portfolio with reinvested dividends may have done very well until 2007, but would have fallen by nearly half in March 2009. And while it did recover steadily from there, it took until late 2012 to climb out of this deep hole. The biggest problem would have been the temptation to change course at every point along the way.

This is where being diversified can help. A portfolio consisting of 60% bonds and 40% stocks recovered its full value in only 11 months from the market bottom – an amazing fact. It has performed well since then, even keeping pace with the all-stock portfolio through late 2016. By definition, it has also declined far less in recent weeks.

That being said, for younger investors an all-stock portfolio can definitely pay off handsomely over the long-run because of the sheer number of years invested.

A more aggressive portfolio consisting of 60% stocks and 40% bonds would have recovered by Oct 2011, about two and a half years after the bottom. It also kept pace with the all-stock portfolio until late 2016, and with recent market volatility, is still quite close.

Those who held only bonds for safety, rather than as an appropriate asset allocation, fared well in the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis. However, it’s clear that even in an unprecedented period of falling rates and policy easing, this portfolio provided little long-term growth.

While the future is uncertain and the causes unique, there have been many market pullbacks and bear markets in the past. In each case, the best response for long-term investors has been to hold diversified portfolios and stay the course.

Our portfolios are carefully crafted to prepare for exactly these events. Trusting in this preparation is the best approach for achieving financial goals.

Below are four charts that help to put the bear market pullback in perspective.

1. Diversification is the best way to immunize a portfolio against uncertainty

Different asset allocations performed uniquely after the global financial crisis. Holding a mix of stocks and bonds not only helped to cushion the initial fall, resulting in a faster recovery, but kept pace with an all-stock portfolio for years. Balanced portfolios have also helped to stabilize investor returns in recent weeks.

2. The spread of coronavirus is still uncertain

Global confirmed cases of COVID-19 have accelerated as the coronavirus spreads through Europe and now the U.S. Health officials have communicated that the path of the lines above will depend heavily on the public response. This has created significant uncertainty for markets and investors.

3. Major indices are officially in bear market territory

Major stock market indices fell into bear market territory last week – commonly defined as a decline of 20% from recent peaks. However, deep, prolonged bear markets often only occur alongside recessions and protracted economic weakness. While this is possible depending on the outcome of the coronavirus, we are not at that point just yet.

4. It’s important to keep this market decline in perspective

It’s important to keep this bear market pullback in perspective. Historical bear markets have been much worse because of economic weakness. Still, even with the tech bubble and 2008 financial crisis, markets tend to recover once there is clarity and growth resumes. Long-term investors seeking to achieve financial goals over years and decades should keep recent market swings in context, shown in the chart above.

As the old cliche goes, “it will probably get worse before it gets better.” But, it WILL get better.

Source: Clearnomics

Recent Posts

2nd Quarter 2025 Market and Economic Review

The Market Reaches All-Time Highs

Last Week on Wall Street: Broad-Based Market Rally [June 30-2025]

Subscribe to Our Blog

Shareholder | Chief Investment Officer