Investors have long recognized that the reasons why companies elect to go public include access to greater fundraising opportunities, improved liquidity for investors, and/or a lower cost of capital. More recently, however, investors have considered the implications related to how companies go public.

Historically, the most common path to enter public markets was through an initial public offering (IPO), and while IPO activity remains vibrant, entryways such as direct listings and special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) have drawn fresh attention. Consequently, investors have been forced to evaluate what, if any, impact these roads less traveled may have on investment decisions. We examine IPOs, SPACs, and direct listings and show that, although each route is characterized by unique terrain, regardless of the path to public markets, the end result is a new public company trading in competitive and liquid equity markets.

Traditional IPOs

In a traditional IPO, the company issuing new equity hires an investment bank to provide underwriting and advisory services for the offering. The investment bank helps pitch the company to potential investors, commonly via what’s known as a roadshow, in an effort to introduce the company to investors, drum up demand for the shares, and subsequently formulate an initial offering size and price that reflect investor interest. Investors awarded an allocation purchase shares through a primary market transaction, following which the shares are listed on an exchange and available to trade.

IPOs represent the most familiar portal to public markets, and while activity levels can vary with market conditions, they remain a popular thoroughfare. Research highlights a few IPO features that can impact aftermarket pricing, such as underwriter pricing support and shareholder lockup agreements.

SPACs

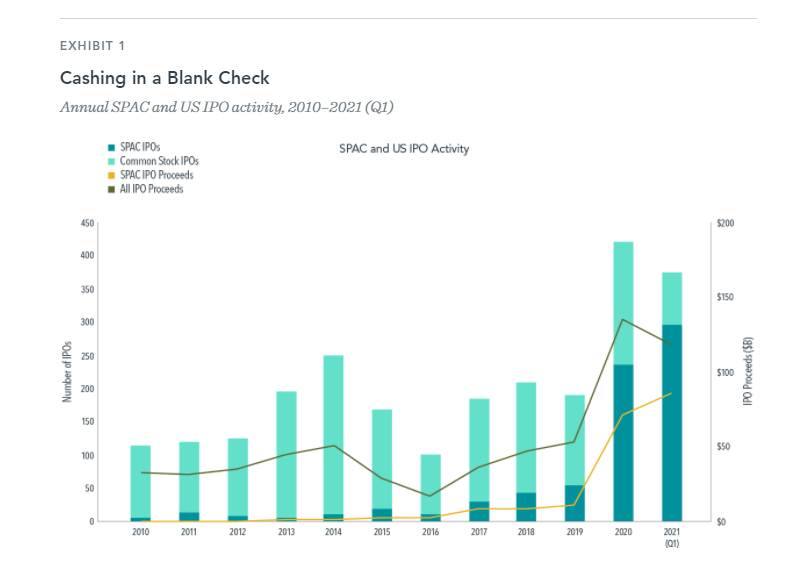

SPACs are a modern version of a “blank check” company designed to use cash raised in an IPO to merge with or acquire an operating company. When the target is a private company, the transaction works like a reverse merger, allowing the private firm to enter the public market. While the vehicle has been around for decades, SPAC activity rose to new heights in 2020 and continued to outpace historical levels through the first quarter of 2021.

For example, Exhibit 1 shows that SPACs raised over $150 billion in total capital across more than 500 SPAC IPOs during the 15-month period ending in March 2021. To put those figures in context, the recent SPAC activity levels exceeded those of concurrent common stock IPOs in both volume and proceeds, as well as the aggregate SPAC totals over the preceding 10-year period.

The current fad has placed SPACs under the spotlight, but the use of blank check companies as a path to public markets has also been in vogue at various times in the past. Therefore, it is important that investors understand the vehicle’s mechanics and the associated price discovery process, regardless of whether current activity levels are sustainable.

First, unlike a traditional offering where issuers hold discretion over the use of funds, the money raised in a SPAC IPO is held in a trust until a target company is identified and a subsequent business combination, or the de-SPAC transaction, occurs. Following shareholder approval of the transaction, the SPAC operators can access the capital to help fund the acquisition or merger. If no deal occurs within a specified period, typically two years, the SPAC is liquidated and the cash held in the trust is returned to shareholders.

Another common SPAC feature allows investors to redeem their shares in exchange for the initial offering price plus interest prior to the completion of the proposed de-SPAC transaction, effectively serving as a backstop for the share valuation. As a result, SPACs typically trade near their IPO price until a deal is announced. Once a deal is completed, SPAC shareholders’ ownership in the shell company is swapped for a stake in the new public operating company, and the shares trade subject to the same pricing mechanisms in effect for the broader public equity marketplace.

Direct Listings

Another avenue used to enter public markets is a direct listing, in which a private company lists its equity shares directly on an exchange without conducting an underwritten offering. Recent modifications to the eligibility requirements by both the NYSE and NASDAQ served to expand access to the direct listing corridor. This notably allowed for a few well-publicized new listings, like Spotify and Slack, though there have only been a handful of direct listings in total in recent years. However, the direct listing process continues to evolve, and new innovations, such as the ability to raise capital via a direct listing, have emerged that may attract additional entrants.

Before shares are made available to trade on a public exchange, the direct listing company and its financial advisor work together to establish the initial reference price based on a recent private-market transaction or an independent valuation. The reference price is then used in an auction process coordinated by a designated market maker on the first day of trading, similar to the way each stock opens for daily trading. Prior to December 2020, direct listings were not permitted to raise capital and the initial liquidity was provided exclusively by early investors and employees. As a result, lockup provisions have not been common, but that may change if firms leverage the direct listing process to raise new capital.

Choosing the Optimal Path

Private companies must evaluate and choose their desired path depending on their targeted objectives and constraints. Companies may choose to go public via a traditional IPO to allow investment banks to pitch the company to a diverse set of potential investors, while other companies may choose to merge with a SPAC to expedite the listing process or because the company believes the SPAC operators provide an additional source of value to the company. Alternatively, companies that don’t want or need underwriter services may choose a direct listing to cut down on the costs associated with going public. Exhibit 2 summarizes the key path characteristics that companies may use to differentiate between the available options.

Implications for Investors

The paths to public markets have come into focus of late due to increased activity in nontraditional entryways, such as SPACs and direct listings. No matter the vehicle chosen to navigate the transit, once a company enters the public marketplace, it becomes subject to the same interactions between the supply and demand for securities that shape equity prices each day.

Investors can take solace in the fact that, whether a company takes the road less traveled or follows the beaten path, we can rely on the drivers of expected returns – size, relative price, earnings and profitability – to point the way forward.

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors

IPOs, SPACs, and Direct Listings: All Paths to the Same Place

Investors have long recognized that the reasons why companies elect to go public include access to greater fundraising opportunities, improved liquidity for investors, and/or a lower cost of capital. More recently, however, investors have considered the implications related to how companies go public.

Historically, the most common path to enter public markets was through an initial public offering (IPO), and while IPO activity remains vibrant, entryways such as direct listings and special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) have drawn fresh attention. Consequently, investors have been forced to evaluate what, if any, impact these roads less traveled may have on investment decisions. We examine IPOs, SPACs, and direct listings and show that, although each route is characterized by unique terrain, regardless of the path to public markets, the end result is a new public company trading in competitive and liquid equity markets.

Traditional IPOs

In a traditional IPO, the company issuing new equity hires an investment bank to provide underwriting and advisory services for the offering. The investment bank helps pitch the company to potential investors, commonly via what’s known as a roadshow, in an effort to introduce the company to investors, drum up demand for the shares, and subsequently formulate an initial offering size and price that reflect investor interest. Investors awarded an allocation purchase shares through a primary market transaction, following which the shares are listed on an exchange and available to trade.

IPOs represent the most familiar portal to public markets, and while activity levels can vary with market conditions, they remain a popular thoroughfare. Research highlights a few IPO features that can impact aftermarket pricing, such as underwriter pricing support and shareholder lockup agreements.

SPACs

SPACs are a modern version of a “blank check” company designed to use cash raised in an IPO to merge with or acquire an operating company. When the target is a private company, the transaction works like a reverse merger, allowing the private firm to enter the public market. While the vehicle has been around for decades, SPAC activity rose to new heights in 2020 and continued to outpace historical levels through the first quarter of 2021.

For example, Exhibit 1 shows that SPACs raised over $150 billion in total capital across more than 500 SPAC IPOs during the 15-month period ending in March 2021. To put those figures in context, the recent SPAC activity levels exceeded those of concurrent common stock IPOs in both volume and proceeds, as well as the aggregate SPAC totals over the preceding 10-year period.

The current fad has placed SPACs under the spotlight, but the use of blank check companies as a path to public markets has also been in vogue at various times in the past. Therefore, it is important that investors understand the vehicle’s mechanics and the associated price discovery process, regardless of whether current activity levels are sustainable.

First, unlike a traditional offering where issuers hold discretion over the use of funds, the money raised in a SPAC IPO is held in a trust until a target company is identified and a subsequent business combination, or the de-SPAC transaction, occurs. Following shareholder approval of the transaction, the SPAC operators can access the capital to help fund the acquisition or merger. If no deal occurs within a specified period, typically two years, the SPAC is liquidated and the cash held in the trust is returned to shareholders.

Another common SPAC feature allows investors to redeem their shares in exchange for the initial offering price plus interest prior to the completion of the proposed de-SPAC transaction, effectively serving as a backstop for the share valuation. As a result, SPACs typically trade near their IPO price until a deal is announced. Once a deal is completed, SPAC shareholders’ ownership in the shell company is swapped for a stake in the new public operating company, and the shares trade subject to the same pricing mechanisms in effect for the broader public equity marketplace.

Direct Listings

Another avenue used to enter public markets is a direct listing, in which a private company lists its equity shares directly on an exchange without conducting an underwritten offering. Recent modifications to the eligibility requirements by both the NYSE and NASDAQ served to expand access to the direct listing corridor. This notably allowed for a few well-publicized new listings, like Spotify and Slack, though there have only been a handful of direct listings in total in recent years. However, the direct listing process continues to evolve, and new innovations, such as the ability to raise capital via a direct listing, have emerged that may attract additional entrants.

Before shares are made available to trade on a public exchange, the direct listing company and its financial advisor work together to establish the initial reference price based on a recent private-market transaction or an independent valuation. The reference price is then used in an auction process coordinated by a designated market maker on the first day of trading, similar to the way each stock opens for daily trading. Prior to December 2020, direct listings were not permitted to raise capital and the initial liquidity was provided exclusively by early investors and employees. As a result, lockup provisions have not been common, but that may change if firms leverage the direct listing process to raise new capital.

Choosing the Optimal Path

Private companies must evaluate and choose their desired path depending on their targeted objectives and constraints. Companies may choose to go public via a traditional IPO to allow investment banks to pitch the company to a diverse set of potential investors, while other companies may choose to merge with a SPAC to expedite the listing process or because the company believes the SPAC operators provide an additional source of value to the company. Alternatively, companies that don’t want or need underwriter services may choose a direct listing to cut down on the costs associated with going public. Exhibit 2 summarizes the key path characteristics that companies may use to differentiate between the available options.

Implications for Investors

The paths to public markets have come into focus of late due to increased activity in nontraditional entryways, such as SPACs and direct listings. No matter the vehicle chosen to navigate the transit, once a company enters the public marketplace, it becomes subject to the same interactions between the supply and demand for securities that shape equity prices each day.

Investors can take solace in the fact that, whether a company takes the road less traveled or follows the beaten path, we can rely on the drivers of expected returns – size, relative price, earnings and profitability – to point the way forward.

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors

Recent Posts

Last Week on Wall Street: Broad-Based Market Rally [June 30-2025]

5 Key Market Insights for the Second Half of 2025

Planning for Rising Health Care Costs and the Role of HSAs

Subscribe to Our Blog

Shareholder | Chief Investment Officer